Cranial cruciate ligament rupture in dogs

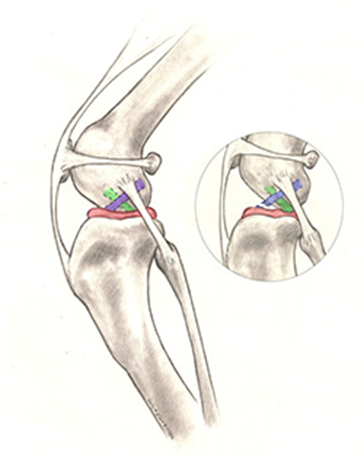

The cranial cruciate ligament (or CrCL, see Figure 1) is one of the most important stabilizers inside the canine or feline stifle (also called ‘knee’) joint, the middle joint in the back leg. In humans the CrCL is called the anterior cruciate ligament (or ACL). The CrCL is the major stabiliser of the stifle, acting to prevent shear (backward-forward movement), excessive rotation and hyperextension. The meniscus (see Figure 1) is a ‘cartilage-like’ structure that sits in between the tibia and femur. It serves many important functions in the joint such as shock absorption, proprioception and load bearing and is frequently damaged when the CrCL is injured. Rupture of the CrCL is one of the most common reasons for canine hind limb lameness, pain and subsequent arthritis. Surgery to stabilise the canine knee following rupture of the CrCL is the most common orthopaedic procedure in the dog.

The development of this problem in dogs is much more complex than in humans. Furthermore, dogs suffer from different degrees of rupture (partial, complete). Hence, the condition is frequently referred to as ‘cranial cruciate disease’(CrCLD) rather than just ‘cranial cruciate ligament rupture’. There is a marked degree of lameness with CrCL disease which inevitably and rapidly causes osteoarthritis and long-term joint pathology and dysfunction.

Causes of cranial cruciate ligament rupture

In humans, trauma (such as skiing, football or netball injuries) is the most common reason for injury of the ACL. This ‘traumatic’ rupture can happen in dogs but in fact is quite uncommon. Most commonly CrCL rupture is caused by a combination of many factors, including aging of the ligament (degeneration), obesity, poor physical condition, conformation and breed. Mostly the ligament injury is a result of subtle, slow degeneration that has been taking place over a few months or even years rather than the result of acute (sudden) trauma to an otherwise healthy ligament. The reason why the ligament gradually degenerates is unknown. A good comparison is a rope on a load exposed to the weather. Over time, individual fibers degenerate, become weak and frayed, the rope thus loses its strength and finally breaks. We frequently see a chronic subtle waxing and waning lameness that becomes an acute severe lameness when the CrCL finally ruptures.

Fig. 1: Illustration of the anatomy of the dog's stifle. The insert shows a ruptured cranial cruciate ligament (also note that the tibia is displaced forward and crushing the meniscus). Cranial cruciate ligament (blue/purple), meniscus (red), caudal cruciate ligament (green).

Incidence

Cruciate disease affects dogs of all sizes and ages and rarely cats. Certain dog breeds are known to have a higher incidence of CrCL rupture (such as Rottweiler, Australian Cattle dog, Newfoundland, Staffordshire Bull Terrier, Mastiff, Akita, Saint Bernard, Golden Retriever, Labrador Retriever and cross breeds of the above listed), while others are less often affected (such as Greyhound, Dachshund, Basset Hound, and Old English Sheepdog). The Rottweiler is 5 times more likely to suffer CrCL rupture than other purebreds.

One study found an increased risk of CrCL disease in female and in male and female neutered dogs, another found an increase in female dogs (entire or neutered). These findings, however, were not found in various other studies and therefore do not alter the current neutering recommendations as the benefits of neutering far outweigh this possible risk.

Risk factors of cranial cruciate ligament rupture

Poor physical condition and excessive body weight are risk factors for the development of CrCL disease. Being obese increased the risk by four times compared to dogs of normal bodyweight. Both factors can be influenced by pet owners (see prevention).

Other risk factors (co-morbidities) include conformational deformities such as genu varum (bowleg) or genu valgum (knock-knee), and medial patellar luxation (slipping knee-caps). Age is also a risk. The peak incidence is in dogs 7-10 years old. Dogs less than 2 years old have a lower incidence, yet large breeds were over-represented for that age category, supporting the theory that large dogs rupture the CrCL at younger ages. Bilateral CrCL rupture is seen up to 37% of dogs. This incidence climbs to 59% if radiographic signs of inflammation and osteoarthritis are seen in the opposite stifle. Currently, the exact aetiology (causes) and pathogenesis of canine CrCL rupture is undefined and controversial.

Clinical signs

As previously mentioned, progressive degeneration of the CrCL from very mild partial tearing to a complete tear in the later stages of the disease is common in dogs. Because of this progression, you may not notice a severe lameness initially, especially if both knees are affected. One common symptom is that dogs will not sit ‘square’ anymore but rather put their leg(s) out to the side when they sit down. You may also observe that your dog has difficulty rising, trouble jumping into the car as well as a decreased activity levels. Muscle atrophy (decreased muscle mass in the affected leg), decreased range of motion, a popping noise (which may indicate a meniscal tear) and swelling on the inside of the stifle (fibrosis or scar tissue) are other signs. Many dogs will shift their weight away from the damaged leg when they stand but the lameness can be less obvious during walking especially with partial tears of the CrCL. When a partially damaged ligament ruptures completely or the meniscus becomes damaged your dog may rapidly progress to become non-weight bearing lame and may hop on three legs. This change in lameness may happen suddenly, usually without major trauma (a minor traumatic event may cause the partially torn ligament to rupture completely). Dogs with chronic (late stages) of CrCL disease usually show symptoms associated with arthritis (decreased activity, stiffness, unwillingness to play, pain etc.).

When do I seek veterinary advice?

It is advisable to contact your veterinarian if your dog shows an obvious marked lameness that persists for longer than a 2-3 days or is in obvious pain. Sudden mild lameness can be due to a soft tissue injury which may resolve within a couple weeks. If the lameness is minor and no significant pain is associated with it, you may rest your animal (no off-leash activity) for a few days and see whether the lameness disappears. If the lameness continues or worsens then veterinary advice should be sought. Aspirin or other over the counter medications should not be given since they be may be harmful to your pet. As a general rule, it is always better to have your animal evaluated by your veterinarian.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is accomplished by a combination of observation of your dog’s gait, palpation of the knee and radiographs (x-rays). This will allow the veterinarian to determine if the lameness is due to CrCL rupture or some other hind leg problem such as hip dysplasia, fractures or dislocations, slipping patella (keecap), spinal disease, neoplasia (cancer), OCD (cartilage disease) or common calcanean tendon (achilles) tendon injury.

Specific palpation techniques that veterinarians use to confirm CrCL disease are the ‘cranial drawer test’ and the ‘tibial thrust test’. These tests confirm abnormal motion in the stifle and hence a rupture of the CrCL. Stifle X-rays are usually taken to confirm the presence of joint effusion (fluid accumulation in the joint which indicates that there is a problem within the joint), the degree of arthritis, to aid in surgical planning and to rule out concurrent disease conditions as mentioned above. X-rays do not show the status (i.e. intact or damaged) of the CrCL or the meniscus since those structures cannot be seen. Therefore, it is crucial that the surgeon evaluate both structures (meniscus and the cruciate ligament) when performing the surgical repair chosen. For certain treatments (osteotomies such as TPLO, TTA etc) specific X-rays are required and hence your surgeon may need to repeat radiographs of the stifle even if your veterinarian has already taken some.

With early partial tears, it can be more difficult to obtain a definitive diagnosis and may sometimes require advanced imaging such as MRI or surgical exploration to physically look at the ligament.

Prevention

As mentioned previously obesity and poor physical condition are risk factors for the development of CrCL disease. If your dog is overweight, a weight loss program is essential.

To accomplish a good fitness level regular activity and avoiding intermittent excessive activity by usually inactive dogs (‘weekend warrior syndrome’) is advised. Regular exercise will also help to avoid obesity. Mostly obesity is associated with overeating, thus keeping your dog lean by sensible diet restriction and moderate regular activity can save you and your dog an extremely worrying time. Joint supplements may also be given, however, there is no data to show that it prevents CrCL disease.

Treatment

Surgical stabilisation of the stifle is the treatment for CrCL disease. Any alternative is merely palliative and will fail over time leading to chronic deteriorating osteoarthritis and associated chronic joint pain and limb dysfunction.

Early CrCL disease with minor partial rupture usually progresses to complete rupture over time. Early surgical intervention is generally recommended to improve limb function and to slow down progression of arthritic changes. Some dogs limp occasionally, whereas some dogs limp all the time, some seem to recover without medical intervention. Sometimes, recovery may simply imply the dog’s ability to adapt to the injury. We all know dogs are amazing with their ability to adapt to pain and injury. But even though dogs can adapt to some degree, one day the wear and tear will leave your dog debilitated and painful. Conservative management with rest and medication may result in temporary improvement of clinical signs; however, it almost always ends up in eventual decline of limb function as deterioration continues to progress as the joint becomes less stable, more painful, and more dysfunctional. The eventual outcome is non-weight bearing lameness due to a complete ligament rupture. By this time the osteoarthritis within the joint and periarticular inflammation is more severe, which prolongs recovery after surgery and is associated with poorer long-term outcomes. Therefore, long term conservative management of CrCL rupture is recommended only for geriatric or systemically ill patient that cannot undergo general anaesthesia and surgery.

Surgery

Surgical treatment is recommended for CrCL rupture since it is the only way to permanently control the instability in the stifle joint and to evaluate the structures within the joint. In other words, surgery addresses the two major problems: stifle instability because of loss of the CrCL and damage to the medial (inside) meniscus commonly seen in conjunction with CrCL rupture. The meniscal problem will be addressed by your surgeon by removing the damaged parts of the meniscus when performing surgery to stabilise the knee. To address stifle instability many surgical treatment options are available to choose from. These different techniques can be divided into two groups based on different concepts:

- Those that render the ligament redundant by cutting the tibia and re-aligning the forces acting on the stifle joint (osteotomy techniques),

- Those that aim to replace the deficient ligament (suture techniques).

Osteotomy Techniques - require a bone cut (osteotomy) which changes the way the muscles act on the stifle joint and prevents abnormal tibial motion (sliding forward) as the dog puts weight onto the leg. Stability of the stifle joint is achieved without replacing the CrCL itself but rather by changing the biomechanics of the knee joint. These procedures come with many names (acronyms) such as TPLO, CWO, TLO, CBLO, TTA, TTO, MMP. All osteotomies aim to render the stifle stable, independent of the CrCL (render the CrCL redundant). All need to have the bone stabilised with a bone plate or some other device to allow the cut bone to heal. The osteotomy techniques have been proven to provide a far superior long-term outcome (limb function and less progression of arthritis) in dogs of all weight / size categories compared to traditional suture techniques. These techniques are based on two methods of achieving stifle stability –

TPLO (tibial plateau levelling osteotomy) or variants CWO, TLO, CBLO, reduce the tibial plateau bone slope until it attains a relatively level orientation that puts the weight bearing plateau at approximately 90 degrees to the attachment of the quadriceps muscles and allows the stifle to be stable without the shear across the joint when placing the paw.

TTA (tibial tuberosity advancement) or variants TTO, MMP advances the front of the tibia, called the ‘tibial tuberosity’ until the attachment of the quadriceps muscle, on the tibial tuberosity, is oriented approximately 90 degrees to the tibial plateau (notice that this is simply another way to accomplish the same orientation as the TPLO).

The decision between TPLO and TTA type techniques is based on individual patient characteristics, concurrent problems (especially patellar luxation), surgeon experience and preference, etc. In general, similar outcomes are achieved with all techniques yet the anatomic configuration of some dog’s stifles may not lend a particular technique safe or effective for that individual.

Suture Techniques can be divided into intra-capsular (within the joint) and extra-capsular (outside the joint) procedures. In humans intra-capsular replacement of the ACL (using local tendon replacement graft) is the most common procedure. This approach has been studied extensively in dogs and found not to be successful mainly because of the difference in anatomy and underlying disease process. However, many companies and surgeons are revisiting this possibility utilizing novel developments. Because of the disappointment with intra-capsular techniques to date, suture techniques are currently performed in an extra-articular (outside the joint) fashion in dogs. The most performed extra-capsular technique is the DeAngelis technique or ‘Lateral Stabilizing Suture’ technique which utilizes strong suture material that is placed just on the outside the joint capsule.

While there are many variations of this technique (different suture materials, ways to tie the suture, how to attach the suture to the bone etc.), the general concept of this procedure is to replace the function of a defective CrCL with a synthetic material on the outside of the joint. This is accomplished by utilizing a strong suture placed in a similar orientation to the original cruciate ligament. The suture needs to stabilise the stifle joint, while allowing normal knee movement, until organized scar tissue can form and assume the stabilising role. The most common complications after this procedure involve failure of the suture (with return of instability) and progressive development of arthritis. Suture failure tends to be more common in active or heavier dogs. The main advantage of this technique is the lower initial cost. Some of the newer techniques such as Tight Rope, OrthoZip or Swivel Lock possibly improve long term stifle stabilisation and outcomes.

The disadvantage of suture techniques is that they reduce the range of motion of the stifle and its ability to naturally internally rotate as it flexes. The progression of arthritis is greater following these techniques compared to the osteotomy techniques and the risk of a poorer outcome is higher.

Complications

Of CrCL disease: Unfortunately, neither human nor veterinary surgeons can completely restore normal stifle joint anatomy and function. Even with surgery some progression of arthritis is expected. It is important to understand that arthritis is a non-reversible disease and hence everything should be done to prevent its development or progression. Therefore, two steps are crucial when treating CrCL disease:

1. Surgical repair

2. Medical management long-term of arthritis. Weight and exercise management are of utmost importance. Long term use of nutraceuticals or the disease modifying drugs of osteoarthritis (DMDOA) such as fish oils, green lipped muscle extracts, glucosamine/chondroitin supplements and pentosan polysulphate injections.

The second most common complication caused by CrCL rupture is tearing of the meniscus. Due to the instability in the knee joint, the inside (medial) meniscus frequently gets damaged. This can happen during the initial injury, in the time while waiting for surgery or possibly after surgical repair of the CrCL. Meniscal damage in dogs is addressed by removing the damaged parts of the meniscus since it is too small to repair. A meniscal tear is very painful and if a damaged meniscus is left in place the animal will not regain full function. Therefore, removal of the damaged parts of the meniscus (if present) will be performed by your surgeon when he or she performs the procedure chosen to address the knee instability , or during a later procedure if it occurs after surgery.

Of surgery: Complications can be related to anaesthesia, as with any surgical procedure, or specific to the procedure itself. Major procedural complications are infection, a late meniscal tear, dislocation of the patella (kneecap) and ongoing or recurrent instability. This latter being much more likely with extra-capsular suture techniques and is extremely rare with osteotomy techniques. Complications specific to the osteotomy techniques include delayed or incomplete healing of the bone, and failure of the bone (fracture) or implants (plate failure, screw pull-out).

Infection may be treated with antibiotics or in some cases surgical irrigation is necessary. Occasionally implants need to be removed after the bones have healed. In the vast majority of animals, the implants remain in place for life and cause no problems at all. Bone or implant failure usually occur in dogs that exercise too much before the bones have healed. These cases along with patients that develop patellar luxation, late meniscal injury or serious loss of stability (suture techniques) will mostly require revision procedures. Serious complications that require a second surgery are rare when the procedures are performed by an experienced surgeon and exercise-restriction guidelines are followed.

Aftercare

Postoperative care at home is critical. The owner takes on a large part of the responsibility for the final outcome. Premature, uncontrolled or excessive activity risks complete or partial failure of the surgical repair. Revision surgery is often required to repair major complications. Proper postoperative care limits activity to leash walking for a minimum of 8 weeks and no running, jumping, rough-housing or off-leash activity. While it is important to control activity, it is also important to maintain muscle mass and joint function (range of motion). Multiple studies have shown that sensible physical therapy speeds the recovery and improves final outcome regardless of the chosen surgical technique.

Prognosis

Long-term prognosis for animals undergoing surgical repair of CrCL rupture is good, with clinical reports of improvement in 75- 85% of the cases treated by extra-capsular techniques and greater than 90-95% in cases treated by osteotomy. Multiple long-term studies have shown that degree of improvement is significantly greater in dogs that have had osteotomy techniques to stabilize the joint. Unfortunately, arthritis progresses regardless of treatment, however, is much slower when osteotomy surgery is performed. Medical management of osteoarthritis to retard its progression is recommended for any dog with CrCL disease regardless of the chosen surgical technique. It is important to realise, that arthritis is a progressive disease and develops relatively quickly in an injured (or damaged) stifle joint. Hence, early surgical repair is advised by most surgeons. It is preferable to treat dogs with partial tears surgically as these patients will have less osteoarthritis and have a decreased the chance of a meniscal tear, and better long-term outcomes.